|

What We’re Up To This Month:

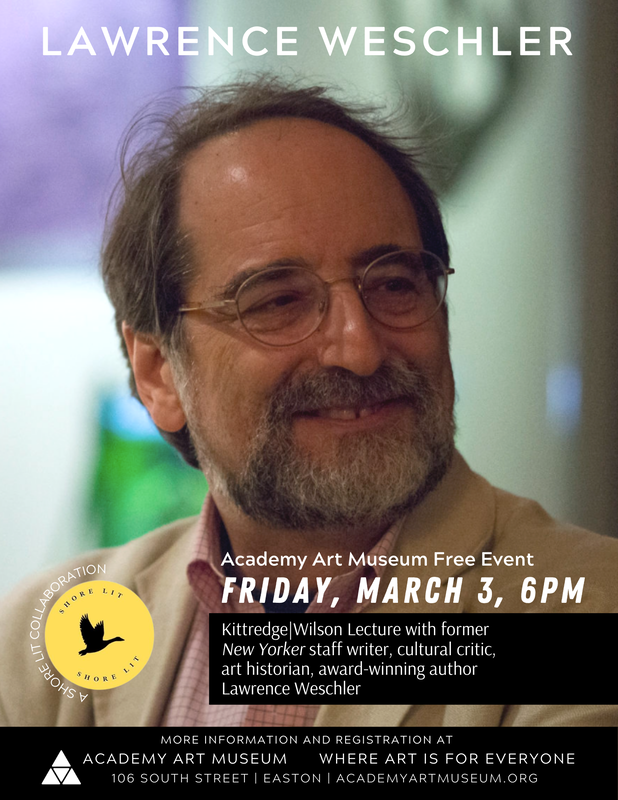

I discovered Lawrence Weschler in 2006 while interning at McSweeney’s, the indie house that had just published his award-winning essay collection Everything that Rises: A Book of Convergences. In it, he explores images, forms, and compositions found in life that seem also to repeat throughout art history: Rothko’s 1969 black and white colorblocks mirroring newspaper covers from that year’s moon landing; Joel Meyerowitz’s photograph of a 9/11 first responder echoing Valezquez’s rendering of the god of war. Art, imitating life, imitating art. The interns at McSweeney’s are not paid, or they weren’t then, but they are invited on their last day to help themselves to a few books from the office stock, which is how I came to own that volume (which is, sadly, now out of print). I flipped through it, fascinated, and then put it on my bookshelf for a decade. It wasn’t until grad school that I truly got to know his writing, when a professor assigned his seminal essay “Vermeer in Bosnia.” In it, he draws connections between the Vermeer paintings he observed hanging in the Mauritshuis Museum and the Yugoslav war-crimes tribunal he was covering nearby in The Hague. He concludes, startlingly and convincingly, that these apparently incomparable things are in fact remarkably similar: they are both about finding interior peace in the face of ravaging violence. This is, I now know, Weschler’s specialty: pairing seemingly unrelated things to revelatory effect. I was stunned by the power of his insights as well as the openness of his prose. In refreshing contrast to the tight-fisted academic exegeses I was used to, Weschler’s essays are rangy conversations, brilliant and accessible, illuminating and human-scaled. I had found my new favorite essayist. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed